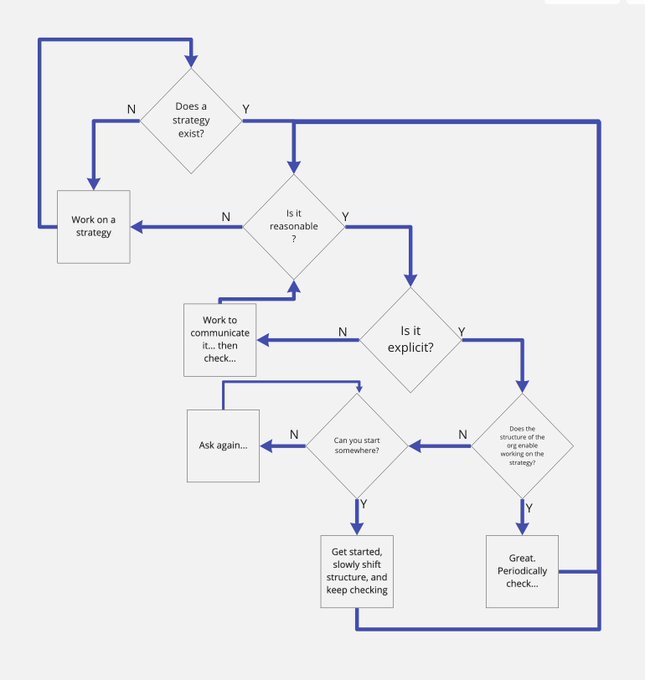

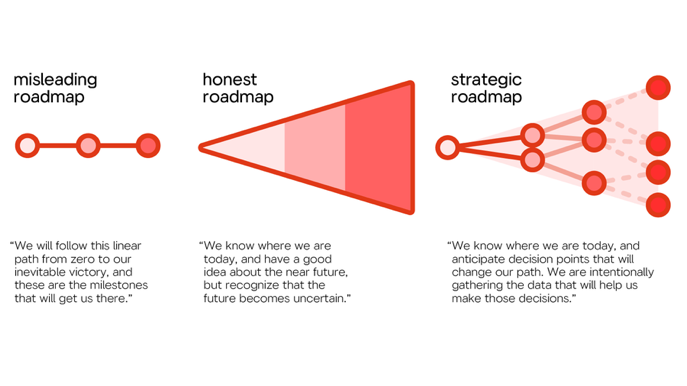

Linear roadmaps are misleading without a crystal ball for seeing the future. A roadmap that recognizes the existence of risk as time goes on is more honest. But an effective PM needs to anticipate possible branches, too – and create clear criteria for following each path.

The second roadmap is a very good start, because it recognizes the existence of uncertainty. But that’s just the first step – the team should be actively working to reduce uncertainty. Make a plan: this is what we need to learn by this milestone to decide what to do next.

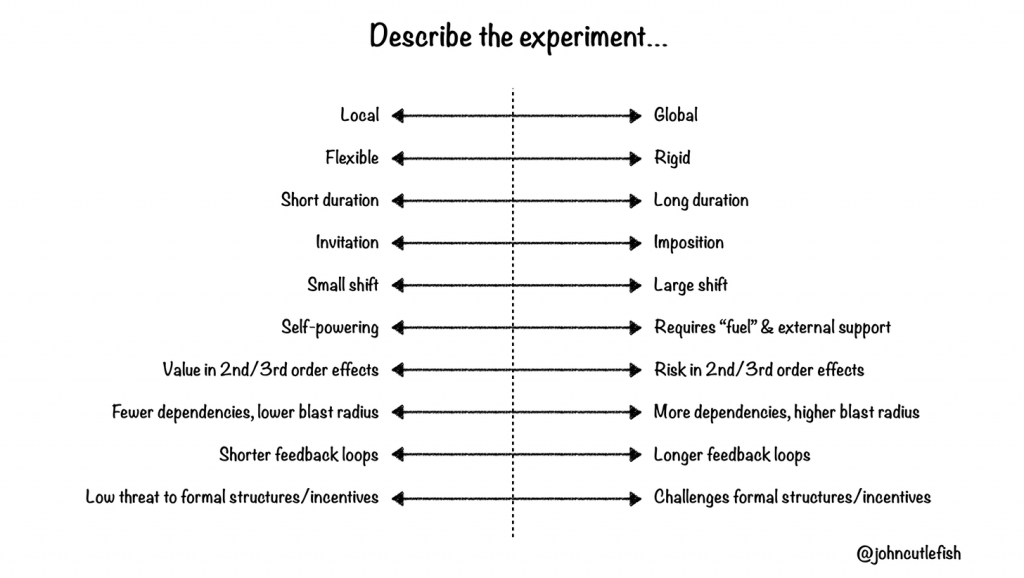

By being explicit about our plans for the future, we are not increasing risk or reducing agility. We open our ideas to critique and experimentation before they are set in stone, so that they can evolve with our understanding of opportunities.

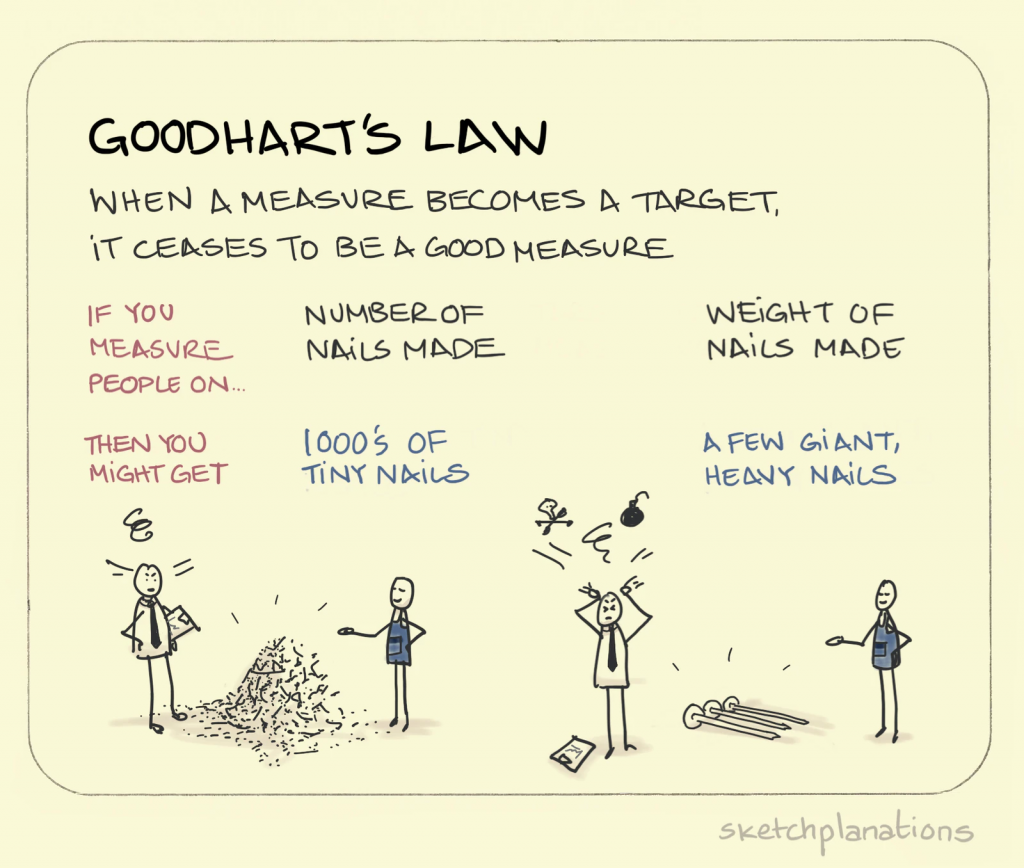

It’s crucial to set success criteria at the beginning of the project: we know that we were successful if this metric is increased by that amount. But you should also have a plan for when it hasn’t, and find out before the last minute whether or not it’s working.

The temporal component in diagram 3 is virtual. The steps are not timeboxed: we know that hypothesis A will be followed by different experiments depending on whether it was confirmed, or we know we may achieve our OKR and will need to do something after, but we don’t know when.

The straight lines might be misleading; the dots are not meant to represent every milestone, merely those decision points that are known to be likely ahead of time. You may wander for some time before you reach them!

The one reason you may want to put features in the branches is if you’ve been pressured by senor management to acknowledge their pet idea. Clearly show that while it’s within the possibility space, there are conditions for reaching it. If they’re not met, it won’t happen.

The great thing about strategic roadmaps is that working backwards from “what do we need to learn” helps easily tie your work to tangible goals. The definition of “good” becomes “does is help us answer the question?” rather than “did management like it?”

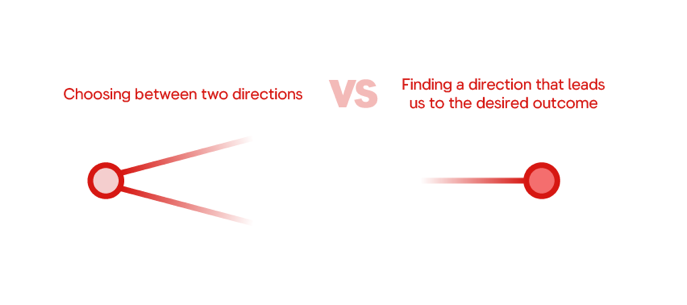

The roadmap tweet lit up on LinkedIn again so it’s time to publish a small clarifying update.

I’m seeing readers focus on the former aspect of the branching paths: “how do we make a decision?” But IMO the latter aspect is far more important: “how do we get where we want to go?”

From https://twitter.com/pavelasamsonov/status/1296818042928861184?s=61&t=rHrwF0m-o8nX1nk6oIOp6A